Debunked: The UK Scrappage Scheme

Scrappage schemes were all the rage a few years ago and some new ones have been talked of more recently, so I thought it was pertinent to talk about the “climate change” credentials of the previous scheme and its effect on the UK car market and specifically British cars.

What Is The UK Car Scrappage Scheme?

The 2009 UK scrappage scheme was the slickly advertised deal that sounded too good to be true. Trade in your road legal but battered old car. Get a £2000 discount off a brand new car. The Government would contribute half and the manufacturer the other half. The aim was to scrap old high emissions cars and put brand new, lower emitting cars on the road instead and reduce overall carbon output.

In total 392,227 cars were scrapped in return for discounts on new “cleaner” cars. It cost the tax payer £400 million, was it all just hot air or did the scrappage scheme have any credentials?

See The Scrappage Scheme Graveyard:

Why Was The Scrappage Scheme Needed?

After the 2008 financial crisis, the sale of new cars in the UK fell by over 20%. Car design and production is a hugely important part of the UK economy, generating turnover of £82 billion and created £18 billion worth of value to the UK economy in 2018. With almost one million people (2018) employed in the sector, a significant drop in sales would have resulted in large scale redundancies.

To prevent redundancies, Alistair Darling introduced the scrappage scheme which promised to aid funding a new car, so long as a road legal car was traded in exchange. The older car would then be scrapped and the Government are seen as heroes by saving the world from pollution.

Did The Scrappage Scheme Cause More Pollution?

The scheme was marketed as removing polluting cars. It also encouraged sales of new cars and scrapping cars that still had use left in them, which is bad irrespective.

“Unless you do very high mileage or have a real gas-guzzler, it generally makes sense to keep your old car for as long as it is reliable – and to look after it carefully to extend its life as long as possible. If you make a car last to 200,000 miles rather than 100,000, then the emissions for each mile the car does in its lifetime may drop by as much as 50%, as a result of getting more distance out of the initial manufacturing emissions.”

Guardian – Extract from “How Bad Are Bananas – The Carbon Footprint of Everything” by Mike Berners Lee

Most of the emissions are from the manufacturing process of a car, it makes sense to maintain existing cars on the road, not scrap them before they reach end of life. The scrappage scheme did both of these, so more pollution was caused from the influx of new cars produced, which would offset any saving in emissions from the exhaust pipe. Crazy.

“The most polluting car is a brand-new one; make a new one from scratch and you’re going to be working against its manufacturing pollution for years, no matter how low its emissions are but classics are a great example of recycling.”

Fuzz Townshend, to Classic Car Weekly

What British Sports Cars Were Lost To The Scrappage Scheme?

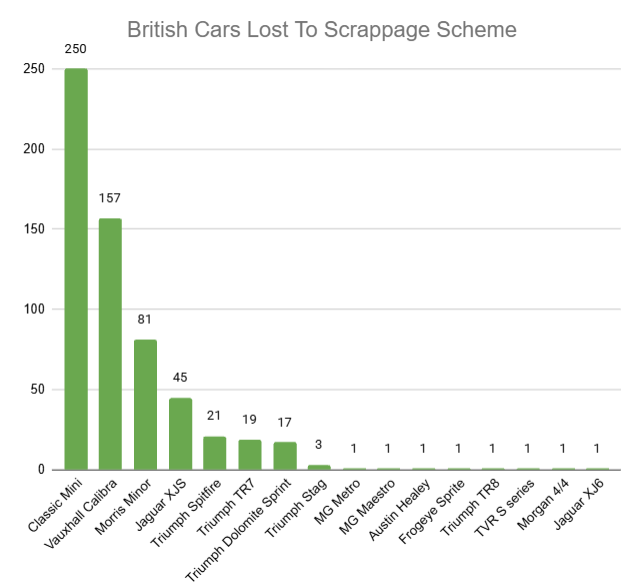

Many classic car clubs were angered and predicted rare classic cars would be traded in to get this bonus. Classic cars aren’t driven as much as more modern cars, so any impact on emissions would be negligible anyway. This resulted in the loss of a potential classic car for no real emissions benefit.

Various rare cars were lost forever, including this selection of British sports cars:

A number of other rarities from other brands were lost including some from Porsche, Peugeot, BMW and Audi. The scrappage scheme has also had the knock on effect of making some mundane cars very rare in the process.

In Summary

Many high emission cars were taken off the road, but many perfectly good cars that had plenty of years left in them were also scrapped. To make matters worse, prices were often raised on the new cars available via the scheme, making the discount a false economy.

The scheme did result in a net fall in emissions -5.4%, but did not take into account the additional emissions generated from the production process of the new cars. Besides, this fall in emissions came shortly after the 2008 financial crisis, so could have been caused by a range of events (eg less people commuting because of job loss after 2008).

The next scheme was funded by manufacturers themselves. This was not done in anyway to improve emissions, but to spur on sales of new cars. Very revealing.

Whenever the concept of a scrappage scheme comes up, it’s usually followed by some message about it helping the environment, but the embodied resources in old cars are never addressed. It’s just a nice way to sell new cars and make people feel good about it.